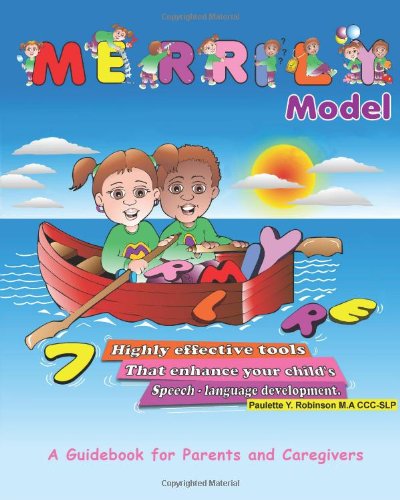

Speech and language impairments are defined as disorders of language, articulation,

fluency or voice which interfere with communication, pre-academic or academic

learning, vocational training, or social adjustment. Source: Florida State Board of

Education Rules.

Sometimes a child has difficulty making speech

sounds correctly. They may distort, substitute with another sound, or omit the sound

completely. If the child is young, he may not be expected to have developed these

sounds yet. These are called developmental articulation errors. If the sounds are no

longer considered developmental, then therapy may e warranted when the following

factors are considered: intelligibility (how easily the speech is understood), interference

with reading, spelling, acquisition of phonetic skills, physical problems that may be

interfering (cleft palate, cerebral palsy), reluctance to communicate within the school

setting due to embarrassment or frustration.

A child with a language disorder may have difficulty with language form, content and

use. Disorders of language form can affect the child’s ability to use word endings to

form plurals, past tense verbs or other grammatical forms they should be using at their

age. A child who has difficulty understanding and choosing words to express ideas has

difficulty with language content. A child with disordered language use does not know

how to use language appropriately in different situations.

The most common voice disorder among children is vocal nodules, a hard callus that forms on the vocal folds. These occur when a child abuses their voice by screaming, frequent throat clearing, and coughing and/or talking at the wrong pitch. A child with vocal nodules sounds hoarse and breathy. Treatment includes education about this disorder as well as methods for reduction in abusive behaviors. Often a child will be seen by an ear, nose and throat (ENT) doctor to determine the origin of the voice disorder.

Children who have difficulty saying sounds, words, and phrases with smooth flow may have a fluency disorder. Many times young children have disfluent speech when they are first beginning to express themselves verbally. It is important that a speech‐language pathologist be consulted to determine if a child is experiencing normal disfluencies or developing stuttering behaviors.

Talk to your child’s classroom teacher and the SLP (Speech‐Language Pathologist) who serves your child’s school. If the problem is also being seen in the classroom, you will be invited to an Intervention Assistance Team meeting with the teacher, SLP and others who may work with your child. You will have the opportunity to discuss your concerns at that meeting and the classroom teacher will discuss educational implications of the communication problem. You and the classroom teacher will be given some intervention strategies to try for a period of time. If those interventions are

unsuccessful, you will sign a “Permission to Evaluate” form. Your child might also be

tested for other learning problems at this time. Once testing is completed, you will be invited to an eligibility meeting to discuss the results of the evaluation and any proposed services that may be offered.

The IEP team (staffing committee) will review all records, observations, and evaluation information to determine your child’s present level of performance and their needs. Consideration will be given to the amount of time the child can benefit from the general education instruction in the classroom, the child’s ability to generalize skills, and all other pertinent information. Our goal is for your child to remain in the general education setting as much as possible.

The first step is to determine if your child’s communication disorder is interfering with

the educational process. If this is the case, then the referral process will be followed.

You may be asked to sign a “Release of Information” form so that the private agency

can release records. The school SLP will then review your child’s current assessments and therapy progress notes to determine if further assessment is needed. Your child will still need to meet district criteria for speech‐language services before an IEP is written.

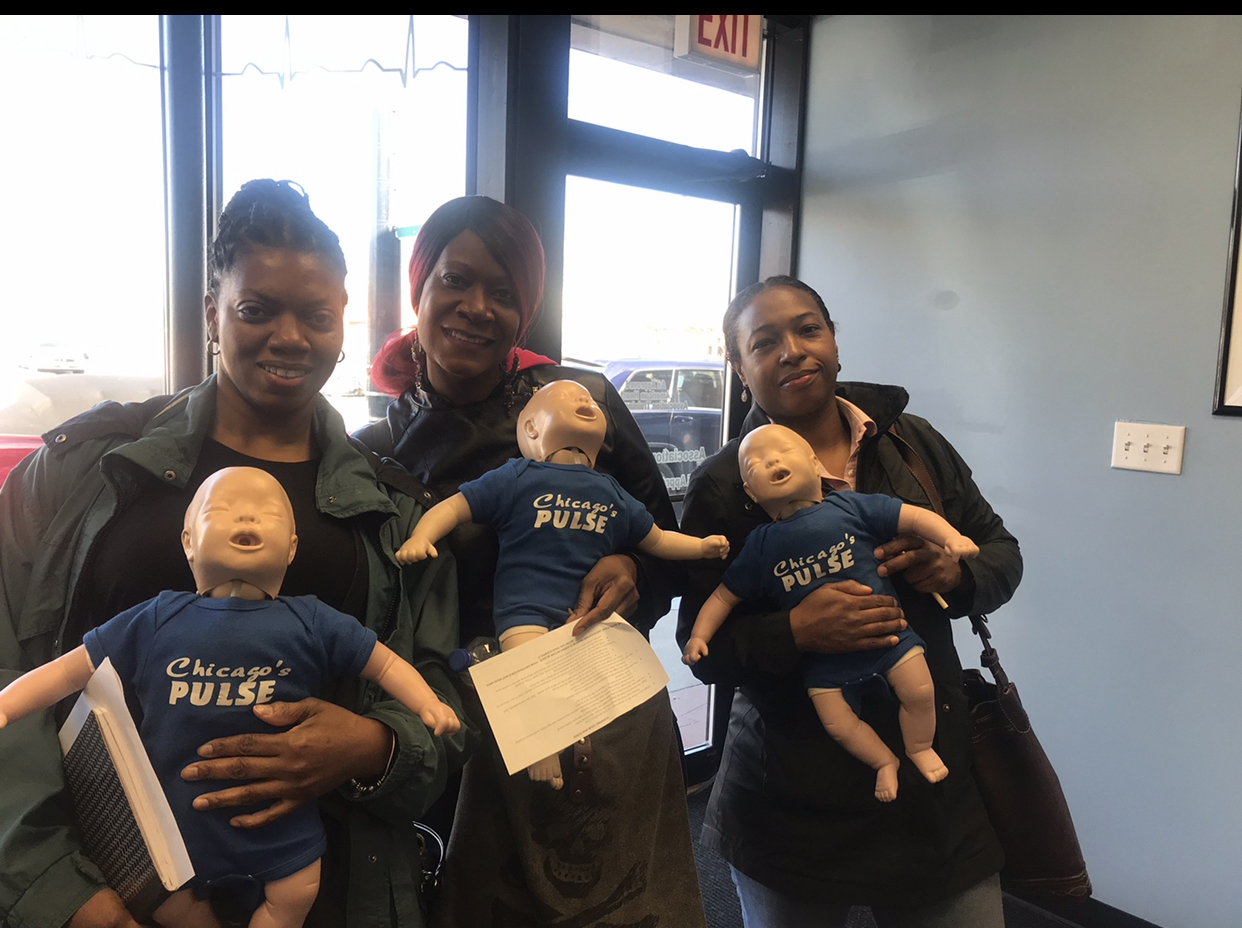

If parents have concerns regarding the speech‐language development of their children

(birth to 3 years), a primary physician or health-care provider should be contacted.

Service coordinators are then notified, and he/she contacts the family and schedules

free evaluations of your child’s development. The evaluations are usually done by a

team of professionals consisting of a speech-language pathologist, an occupational

therapist, a physical therapist, and a developmental therapist. If a child is found to have

a developmental delay requiring early intervention services, the state’s early intervention program works with the family to develop an Individualized Family Services Plan (IFSP). Your service coordinator will be in contact with you during your entire early intervention process.

There are differences in the age at which a child understands or uses specific language

skills. The following list provides information about general speech and language

development.

Compiled from www.asha.org “How Does Your Child Hear and Talk?”

Birth – 3 Months:

- Startled by loud sounds

- Quiets down or smiles when spoken to

- Seems to recognize your voice and quiets down if crying

- Increases or decreases sucking behavior in response to sound

- Makes pleasure sounds (cooing, gooing)

- Cries differently for different needs

- Smiles when they see you

4 – 6 Months

- Moves eyes in direction of sounds

- Responds to changes in tone of your voice

- Notices toys that make sounds

- Pays attention to music

- Babbling sounds more speech-like with many different sounds including, p, b, and m

- Vocalizes excitement and displeasure.

- Makes gurgling sounds when left alone and when playing with you

7 Months – 12 Months

- Enjoys games like peek-a-boo and patty cake

- Turns and looks in direction of sounds

- Listens when spoken to

- Recognizes words for common items like “cup”, “shoe,” “juice”

- Begins to respond to requests (“Come here,” “Want more?”)

- Babbling has both long and short groups of sounds such as “tataupup bibibibibi”

- Uses speech or non-crying sounds to get and keep attention

- Imitates different speech sounds

- Has 1 or 2 words.

12 Months

- Responds to their name

- Understands simple directions with gestures

- Uses a variety of sounds

- Plays social games like peek-a-boo

15 Months

- Uses a variety of sounds and gestures to communicate

- Uses some simple words to communicate

- Plays with different toys

- Understands simple directions

18 Months

- Understands several body parts

- Attempts to imitate words you say

- Uses at least 10 – 20 words

- Does pretend play

24 Months

- Uses at least 50 words

- Recognizes pictures in books and listens to simple stories

- Begins to combine two words

- Uses many different sounds at the beginning of words

2 to 3 Years

- Speech is understood by familiar listeners most of the time

- Understands differences in meaning (go-stop, in-on, big-little, up-down)

- Follows two requests (“Get the book and put it on the table”)

- Combines three or more words into sentences

- Understands simple questions

- Recognizes at least two colors

- Understands descriptive concepts

3 to 4 Years

- Uses sentences with 4 or more words

- Talks about activities at school or at friends’ homes

- People outside of family usually understand child’s speech

- Identifies colors

- Compares objects

- Answers questions logically

- Tells how objects are used

4 to 5 Years

- Answers simple questions about a story

- Voice sounds clear

- Tells stories that stay on topic

- Communicates with other children and adults

- Says most sounds correctly

- Can define some words

- Uses prepositions

- Answers “why” questions

- Understands more complex sentences